Dream at the Helm - Revised

This is a revision that was inspired by Jennifer Lauck. She challenged me to write what I did not want to write. "What are you not saying?" she asked. I really struggled to find a way. And I cried all the way through reading it. But this is the great power of being in the circle of writing women....really amazing. It does take a village to pull us through sometimes. Because it's not about writing. It's about how we grow more truthful and more accurate in rendering our truth.

***

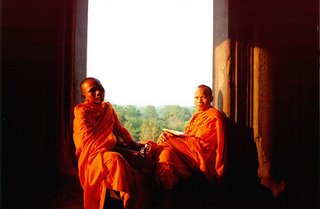

Tibetan nuns whisper in my ear, their melodic syllables weave through this tight mesh of muscle; mid-back down to the sacrum, pain, taut and inflamed. I didn’t want to wait until I was thirty-seven to have a baby. My back - old, devoted workhorse, carried a thousand boxes between seventeen and thirty-seven; now, with the baby, muscles are bungee cords that snap from the wear. I wait way too long before tending to the ache. It’s always been that way.

When the massage therapist runs her elbow down the highway on each side of the spine, she gasps, “Ok, feel this? These are supposed to be three separate muscles, moving in relationship to the others.” I hold my breath, try to remember to let go, but that feels like more work. Breathing is not something I know innately. I have to say: Breathe, Prema. Letting down, bone to table, a fan of nerve-lightning spreads through the hips until I hold again. “On you it’s a bed of rocks,” she moans, and continues to grunt, making sound affects for the tight spots. “Thanks, I get it.”

But I don’t really get it. You’d think I want to be in this body – I came into it three months early, weighing four pounds. In the beginning, on my back, warm light moves across paper-thin eyelids, striations of tiny veins, red rivers illuminated from behind closed eyes. Air purrs from small whirling fan blades and echoes in my ears. Buzzing florescent lights, heat upon my cheeks, tubes down my throat – not even the first impulse to breathe, I am being breathed by machines. I wait there for thirty days, the incubator, but no one comes. No touch. No one says, welcome, this is your body.

So I learn to travel.

Now, face down on the table, I am in the air, over the Atlantic, looking down upon a bug in the landscape. In this direction and that, the expanse of green pasture, vividly burning color of forest, but flat, unpeeled, rolled out for miles and miles. Ireland. I drop down through rain, through thick milky clouds, out into open blue. Down below, closer now, I see a woman. She is alone, small on a wide stretch of road. Head down, heavy-footed. She carries a backpack in the rain, soaked through. She cries. She prays. I hear her. But the words are not new to me. They are my words, spoken twenty years ago, utterly bare.

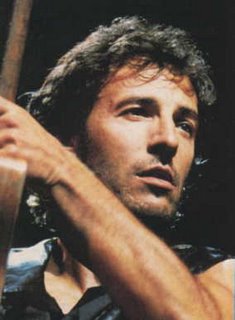

I hover above her. My eyes blur with the recognition that I am looking at myself; young woman who walks the world. Shipwrecked. Weeks ago she runs down the airport corridor, still sore, ribs throb, where he held her down on the staircase that night. Hours and hours, after kicking the door across the room, a knife at her throat, cold steel turns hot and burns. He keeps his nose a half inch from hers, sneers, smiles and haunts her with dangling threats. When the sun was up, a neighbor stands in the doorway. “Get up, Prema, run.” Even blocking the doorway, she runs through a small opening in his legs, out into the morning air, down the steps. She’s still running two days later. Denver International. One hundred feet behind her he clips people like flies, running, screaming, “As long as you breathe, I die.” Her friend makes up the space between them, stopping mid-stride and the man falls to the ground, security closing in on him. “Go, Prema, run. Run, girl. Go!”

She runs all the way to Europe, son of a bitch, that’s how it feels. On the plane, nine hours, thigh muscles trigger and fire. Strong horses, they can’t stop running.

She’s only twenty.

Days ago she sits on the ground, gazing at a vast circle of stones. Finally, rest. Finally, freedom. A guard motions for her to rise, he lifts the rope, and escorts her to the very center. “Why are you letting me do this?” she asks, as tourists point and cackle. “Hurry up,” he says, “I could get in big trouble for this.” And so she walks, and without reservation, presses her forehead against the cold monolith: Stonehenge.

That was enough for one day or one year. Almost enough to keep her going, except for the guy in the back of the bus, who stares at her all the way back to town. Bath, England. Everything in her says no and everything else in her that wants attention says yes, please. He gets off at her stop, smiles, follows her to the front desk. By the evening, tired, shaky, she finds resolve, she’s learning to say no, and settles in to read her book with a warm cup of tea. But the doors at the inn are old, latches old, locks old. She spends the darkest hour of the night until moments before sun up under his weight, saying no, but it doesn’t matter.

She runs to the train station, she runs to the West Coast of England – that’s how it feels. Wretching over the side of the ferry all the way across the English Channel, she can’t escape being in the body, and she wants to escape. Walking the streets of Dublin, 3am, she’s still crying, heading west.

She thinks she’s alone, but I’m right here. Looking, as far back as I can see, ruin. Gazing ahead through time, great falling. But we make it and I need to let her know that there is a great river up ahead, twenty years ahead but just around the bend.

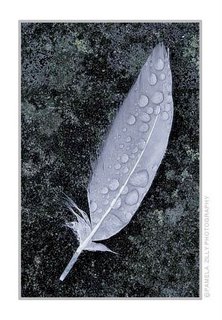

So I call out, first to my friend the wind. Next to the old winged-ones. Finally, to the elixir in the blood of plants that I know. Together they arrive; birds deliver medicine, carried by the wind. And they have a message.

The girl looks up – she hears, no she feels, no, she is embraced by a sensation of many arms around her torso. It’s me, my arms, around the midsection. It’s my mother, I call her because I can do that now. And I tell her just how to approach, just how to place her hands: “Hold her like this,” I say, “just the way she wants it.” She’s only been dead to her for a year, but now, two decades later, even in death, my mother wants to reach her, and I show her. Held together, altogether: mother-daughter-mother embrace.

With the help of all the guardians, I lean close in, pause for a moment by her ear, caressing with breath – the way I rock my baby, and then I whisper: Dear One, all is well. Keep your faith. Let these tears show you a river. All your people traveled down it, and they hold you now as you walk down this lonely road. Feel the path. Find the way. Know how it feels to fall, and in falling, pay attention to the way it feels to rise slowly in appreciation. You will have your body back.

I awaken with a start. Lavender on the forehead, I peel the eye pillow slowly away, and swim, swim, swim back to this place, this room, this table. It takes a full sixty seconds to figure – how to move? I do move. I do get up because I want to, and the way heat is all in my limbs – it’s starting to feel okay. Six thousand nerve endings.